Raúl’s Story

For years I have been fascinated by the rainforests surrounding the Panama Canal. They contain an incredibly rich fauna, exuberant flora and some truly spectacular vistas. Furthermore, parts of these well-conserved forests are only minutes from Panama City. However, as a businessman interested in ecotourism, I could not do anything about it because these lands were part of the Canal Zone or under US military control and, consequently, off-limits for commercial development.

With the signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties in 1977, this began to change, but the Noriega years slowed everything down and caused a backward leap in the Panamanian economy. Who would want to come to Panama with such an unsavory character in power? After the US invasion of 1989–1990, I worked with the new government putting the country back on track, and it wasn’t until 1995 that I was ready to start realizing my dream.

Back then I did not have a clear concept in my mind about what exactly I wanted to do, but I knew the areas around the Canal were unsurpassed in the whole world for ecotourism potential. Where else can you see 380 species of birds in a 24-hour period (a world record)? Where else can you see huge passenger ships navigate through a lush tropical forest? Where else can you see the Panama Canal, a true wonder of engineering and human ingenuity? Only in Panama, of course.

Consequently, in August of 1995, I met for the first time with Dr. Nicolas Ardito Barletta, the recently appointed Director General of the Autoridad de la Region Interoceanica (ARI), the agency of the Panamanian Government in charge of allocating the real estate being transferred to Panama by the United States in compliance with the Torrijos-Carter Treaties. I received enthusiastic support from Dr. Barletta, which was essential to my finally realizing my dream, some two years and countless meetings later.

First I began to explore the area around Gamboa, specifically Pipeline Road, which is renowned worldwide as a superb birding area. Being a birdwatcher myself, I naturally looked for sites in which I could also practice this peaceful and challenging hobby. After several weekends of exploration in which Mantled Howlers, White-faced Capuchins and Titis (Geoffroy’s Tamarins) were my frequent companions, not to mention toucans, trogons, gato solos (coatis) and neques (agoutis), I came across indications of a spot where the US Army many years ago had had some type of installation. The site and a road leading to it appeared on maps and in aerial photos taken 20 years ago, but more recent pictures showed only trees and more trees where the installation had been. Obviously, nature had taken over the area, making it even more interesting.

Having found the “ideal” place for an ecolodge, I approached ARI with the results of my investigations. ARI then had to contact the Panama Canal Commission because the chosen site was within the operating area of the Canal. After several weeks and several letters and memos back and forth, it was found that the site was under still under the control of the US Army, specifically, the US Tropic Test Center. So the ARI had to approach the Army for permission to inspect the site. Again, several weeks passed and several notes and memos were sent to the US Embassy (Treaty Administration), which in turn contacted the Southern Command, which in turn contacted the US Tropic Test Center. Finally, the word arrived: “NO! We need this place”— although it had been abandoned for years.

Back to square one! Undaunted by this setback, I began the search again. This time I explored the area past Gamboa near where the US Air Force had a small landing strip, right next to the Canal. I wanted a spot that could be reached by car and this ruled out the many beautiful islands and coves of Gatun Lake. Again, I spent several weekends walking the area and once even got lost for about two hours, but I found a beautiful spot with a small lake and a spectacular vista of the Canal. This was IT, fantastic!

I approached the ARI once more with the “ideal” spot in the bag and the process began again. Letters, memos, aerial pictures, maps, meetings, you name it…I complied with every request and met with whomever had anything to do with this approval, even remotely, but to no avail. The spot was too close to the Canal and the Commission was not too keen on the idea. I was told to look for another site because it would not be approved.

Back to square one again! I was about ready to quit then. I had been in this search for over a year and I was fed up with bureaucracy. I seriously considered dedicating my efforts to expanding my operations in El Valle de Antón where I had recently completed an ecoturist attraction called the Canopy Adventure. But dreams are worth pursuing, so I kept going.

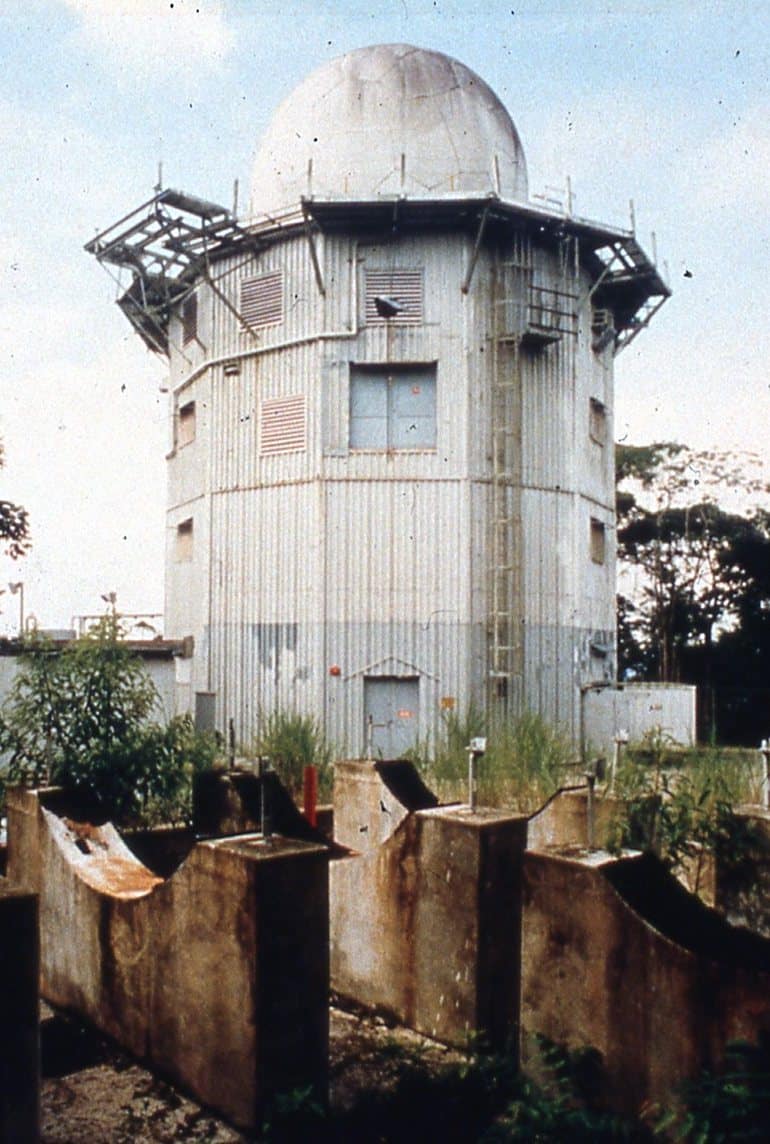

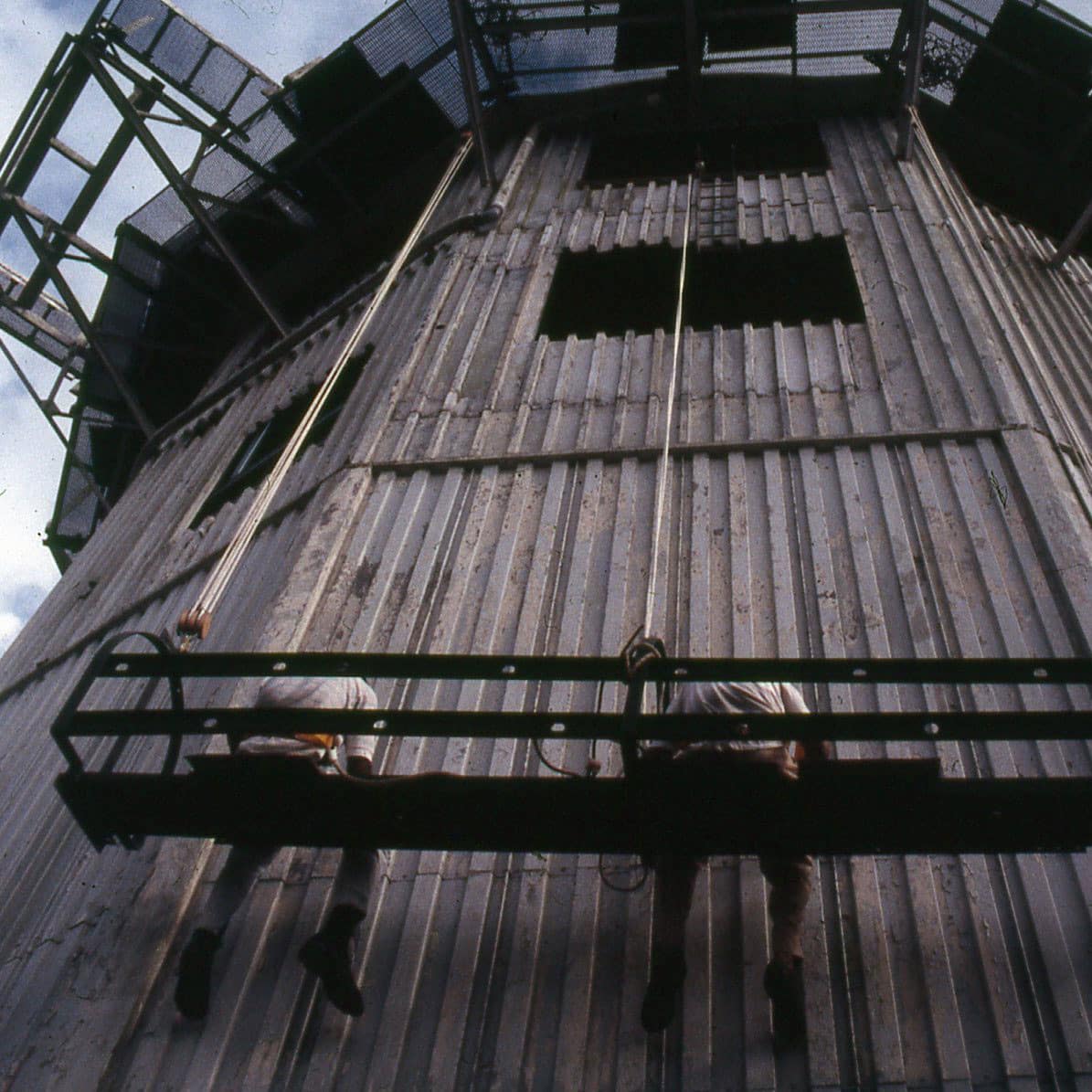

This time, the support of a US employee of the Panama Canal Commission proved to be critical. Tom Duty, Manager of the Real Estate Management Division, said offhandedly at the end of a meeting in which site no. 2 had been turned down: “Raúl, have you ever been to Semaphore Hill? There is a USAF radar tower there and it reverts to Panama in November of this year, take a look at it, you might like it”. I had never even heard of the place…Semaphore Hill…it was not in Gamboa, its name brought to mind images of traffic and streetlights and, frankly, I was despondent, but I decided to take a look at it anyway.

“What the heck,” I thought! I have invested so much time and effort in this project I might as well take a look at this hill. And, after all, as we say in Spanish, “a la tercera va la vencida,” on the third try you win! And win I did!

Two weeks later I visited Semaphore Hill accompanied by Gladys Diaz, who is Tom Duty’s Deputy, several USAF and ARI personnel, and a couple of civilians from the Treaty Implementation Department of the Southern Command. Even though nobody brought the key and we couldn’t go inside the building, I immediately liked the place. I did not know what I was going to do with it but I liked it right away, it was indeed love at first sight!